News

Don't buy the dip: Why some investors think more big market falls are coming

‘There’s no such thing as a bear market without a bear market rally,’ says one fund manager.

When markets were in freefall under the pressure of coronavirus last month, Gregory Perdon was tempted to fall back on a tried-and-tested maxim that has assured investors a healthy profit for the past decade.

“Every portfolio manager is mindful of the mantra to ‘buy the dip’,” said the co-chief investment officer at London-based private bank Arbuthnot Latham. At first, that included him.

“Initially, I thought this would be a V-shaped recovery,” he said — a speedy return to health for the global economy and the capital markets after a short spell of distress triggered at the end of February by virus outbreaks and lockdowns in Europe. “What changed my view was when the Fed came in all guns blazing, and the markets still went red.”

The U.S. central bank slashed interest rates by a full percentage point, among a series of other supportive measures, before markets opened on March 16. The grand intervention was followed by the deepest stock market declines since 1987, triggering Perdon’s change of heart.

Now he focuses his efforts on what he describes as “curbing the enthusiasm” of some colleagues. “There’s no such thing as a bear market without a bear market rally,” he said.

Since their mid-March low, U.S. stocks have gained about 25 per cent, technically lifting them back into a new bull market, albeit one tinged with extreme uncertainty over the outlook for companies and the global economy.

This presents a dilemma for investors. Is it wise to piggyback on the government and central bank support pouring into financial markets and snap up assets while their prices are still beaten up? This could, in years to come, end up being seen as the buying opportunity of a lifetime. Or is the epic shake-out in markets in March just the start of a long, slow decline in riskier assets?

Deep pullbacks are, after all, a common feature of markets in the immediate aftermath of abrupt crises, as was evident in 2001, 2008, and even back to the great U.S. stock market crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression. U.S. stocks did not reclaim their 1929 highs until 1958. Some analysts therefore reckon that the rally since late March is what is often dubbed a “bear market trap”.

Robert Buckland, chief global equity strategist at Citi, points out that a decent rule of thumb is that stock markets fall roughly as much as corporate earnings do. The depth and extent of the global recession indicates that profits should halve this year — but the FTSE All-World index is now back within 20 per cent of its peak.

Some analysts reckon that the rally since late March is what is often dubbed a 'bear market trap'

Fund managers must try to balance the huge scale of central banks’ support — underlined again on Thursday when the Fed announced yet another big support package to the tune of US$2.3 trillion — against economies in deep distress, as seen in a record-breaking acceleration in U.S. job losses.

Not everyone is convinced the stimulus is enough. Bank of America analysts note that U.S. equities have never taken less than six months to find their bottom, once they have tumbled 30 per cent and the economy is in a recession. They therefore predict that markets have further to fall.

“While those banking on a rapid equity market recovery are (expecting) unprecedented stimulus to erase the pain, history would also suggest they may be banking on a miracle,” they wrote in a recent report.

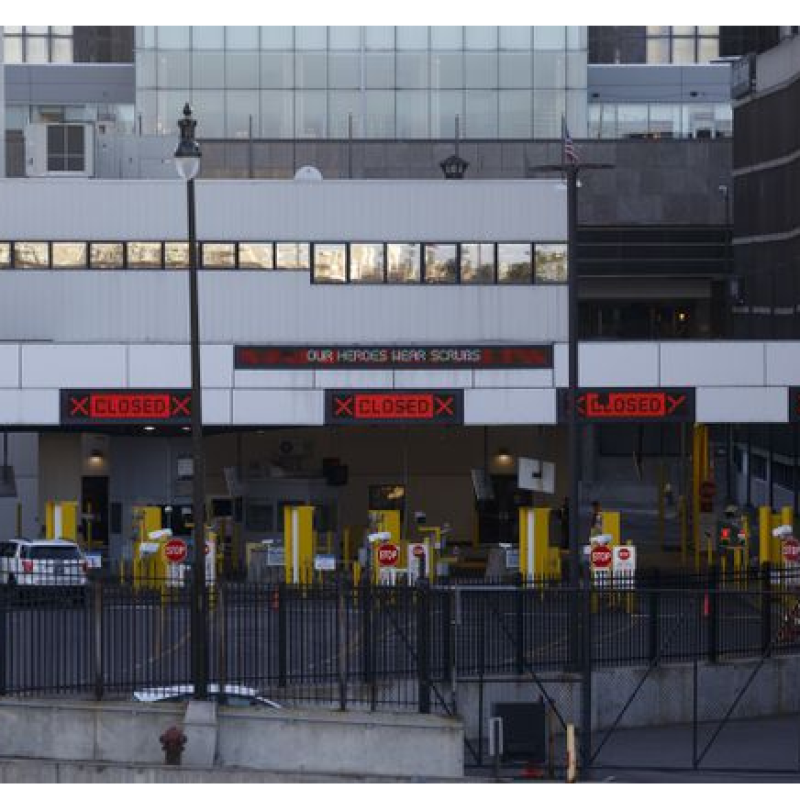

Signs that the coronavirus spread is slowing is not necessarily enough, either. Some analysts point out that while some countries — such as Norway, Denmark, the Czech Republic and Austria — have recently announced plans to gradually end their lockdowns, the economic damage is likely to linger.

Howard Marks, the 73-year-old billionaire founder of Oaktree Capital Management famed for his knack for scooping up bargains at times of economic distress, said in a note this week that with the course of the virus so difficult to predict, and its effects so sprawling, investors should be willing to admit that they simply do not know what happens next.

That is a tough task for a profession that prides itself on making predictions and anticipating their market impact, but “no one can tell you this is the time to buy”, he wrote. “Nobody knows.”

Nonetheless, Marks said that extreme caution was now no longer warranted, given drops in asset prices and the wave of central bank support that has neutralised some systemic risks. He recalled how he and his partner Bruce Karsh snapped up US$450 million worth of corporate debt each week for 15 straight weeks after Lehman Brothers went bust in 2008.

“What I would do is figure out how much you’ll want to have invested by the time the bottom is reached, and spend part of it today,” he wrote. “Stocks may turn around and head north, and you’ll be glad you bought some. Or they may continue down, in which case you’ll have money left to buy more. That’s life for people who accept that they don’t know what the future holds.”

ORIGINAL SOURCE: https://business.financialpost.com/investing/dont-buy-the-dip-why-some-investors-think-more-big-market-falls-are-coming

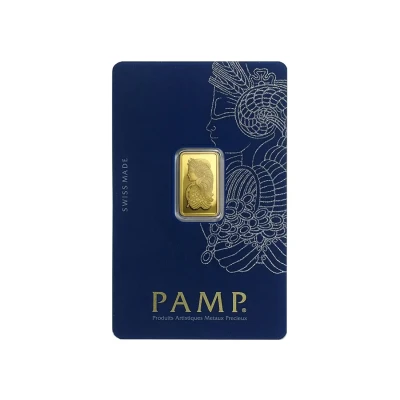

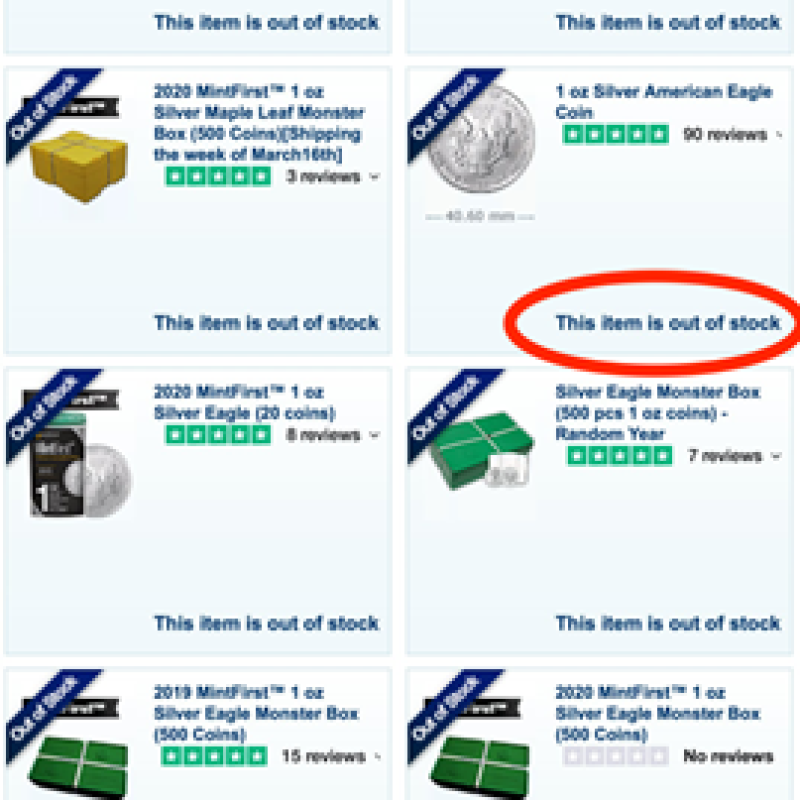

Pamp Suisse

Pamp Suisse